It may be because it doesn’t physically work as required, which is Ok(ish). I mean, if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. But I’m not prepared to give up on all the time I’ve invested in it before I’ve fully explored every possible modification that may make it useable.

Or, and this is the worst one for me, because it just doesn’t look right. In this case I’ve made a perfectly functional item. It does the job it was designed to do. But when I stand back to admire my work, aesthetically it just isn’t quite right. I try to kid myself that it’ll be Ok, but it nags away at me. Every time I look at the bike my eye is drawn to it. It’s spoiling the lines. It isn’t flowing correctly. It’s not creating the look I wanted. Eventually, I can’t take it any more - it has to go. Either way, resigning myself to starting again can be quite painful.

Burt Munro (think World’s Fastest Indian) had a special shelf labelled ‘Sacrificed to the God of Speed’ where all the parts that didn’t quite work were parked. Apparently he shelved parts with equanimity, had a rethink and calmly carried on. It’s not a state of mind that I can easily achieve myself. Usually, for me, it involves some swearing, grumpiness and a little sulking.

Sometimes it’s hard letting go!

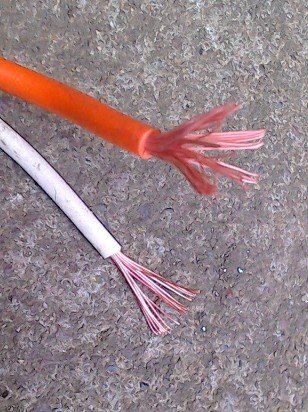

As if dealing with working out which wire goes where isn’t enough of a problem when you're wiring up a bike, you also need to make sure that the connections are good. This isn’t so bad if you’re using new cable, but if you’re working with an old wiring loom, the chances are that stripping back the insulation will not reveal bright, shiny copper wire. Mostly, it’ll be black with copper oxide, or for really old looms, green with verdigris. Either way, if you want to make a good connection (especially if you want to solder the wire) it really needs to be removed.

In my search for an easy way of cleaning up copper cables I tried various household chemicals, but the only one that proved successful was Cillit Bang. It wasn’t exactly, ‘Bang and the copper oxide is gone,’ but I found that about an hour of soaking would do it.

One caveat, the back of the bottle lists vinyl as one of the materials that Cillit Bang shouldn’t be used on, so try to keep it away from the cable’s insulation (although it didn’t seem to have any obvious effect on the insulation of my test pieces).

I first started writing this article after being stunned at the loss of William Dunlop. Subsequently there have also been further casualties at the Southern 100 races. Is the price (in terms of severe injury and loss of life) of these races too high? It is just a sport after all.

Dan Kneen, Adam Lyon, William Dunlop, James Cowton. All have lost their lives at the TT or ‘real’ road races in the last few months. Now I’m a firm believer in letting people make their own choices in life, and I don’t want to see races like the TT or other ‘real’ road racing events outlawed, but is the price (in terms of loss of life) too high?You can’t remove all risk from life, well you could, but then no one would actually do anything, but is it possible to make them safer?

The performance of modern bikes, plus (I think) a change in rider attitude has made the margin for error extremely narrow. The following is an extract from August’s ‘Performance Bike’ magazine. It was written by Michael Rutter’s crew chief.

“To be honest, it does worry me to watch the guys these days. The really quick lads are coming from domestic short circuit racing, and they’re riding the TT like it’s a short circuit. I don’t worry about Rutter - I know he’s giving 95%, and he has a wise head and stacks of experience. However, if I was on Hickman’s or Harrison’s crew, I’d have been shitting myself.”

The phrase often trotted out is, ‘He died doing something that he loved.’ But for very top riders, is that always still true? I’ve heard at least one top rider admit that it’s not the racing that he enjoys, it’s the success that it brings that’s so addictive. And for a few of these riders, it’s also what pays the bills. It’s a job. No racing. No results. No money. If you have nothing else to fall back on, what choice do you have?

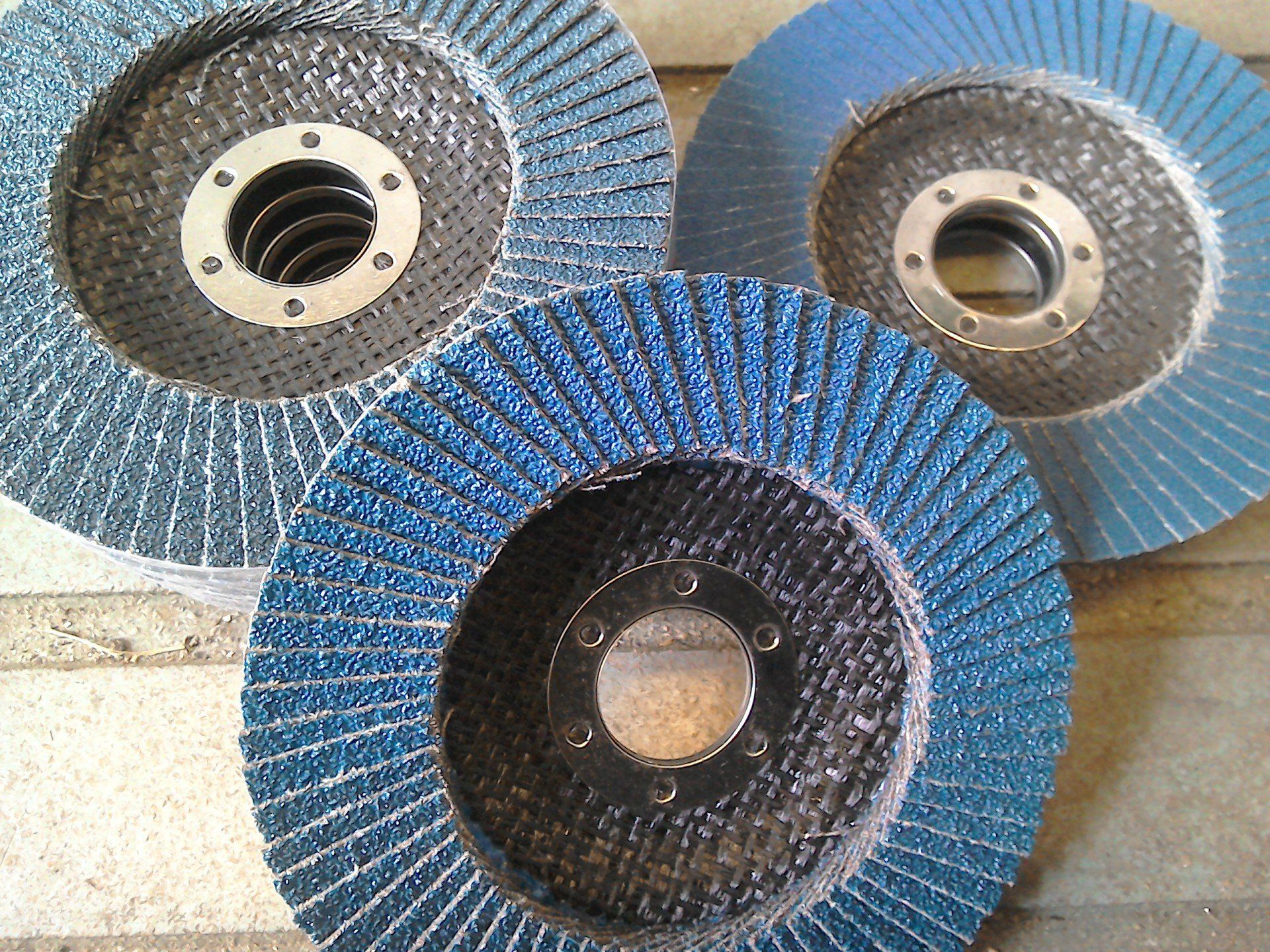

Flap is a bit of a misnomer, since it makes you think that they are, well, a bit floppy. They are in fact quite rigid, but not quite as stiff as a traditional disc, and this is good since they don’t suffer from the same chatter and vibration that you can get with standard discs. Available in different grit sizes, the coarse ones remove material quickly, and the finer ones produce a lovely smooth finish.

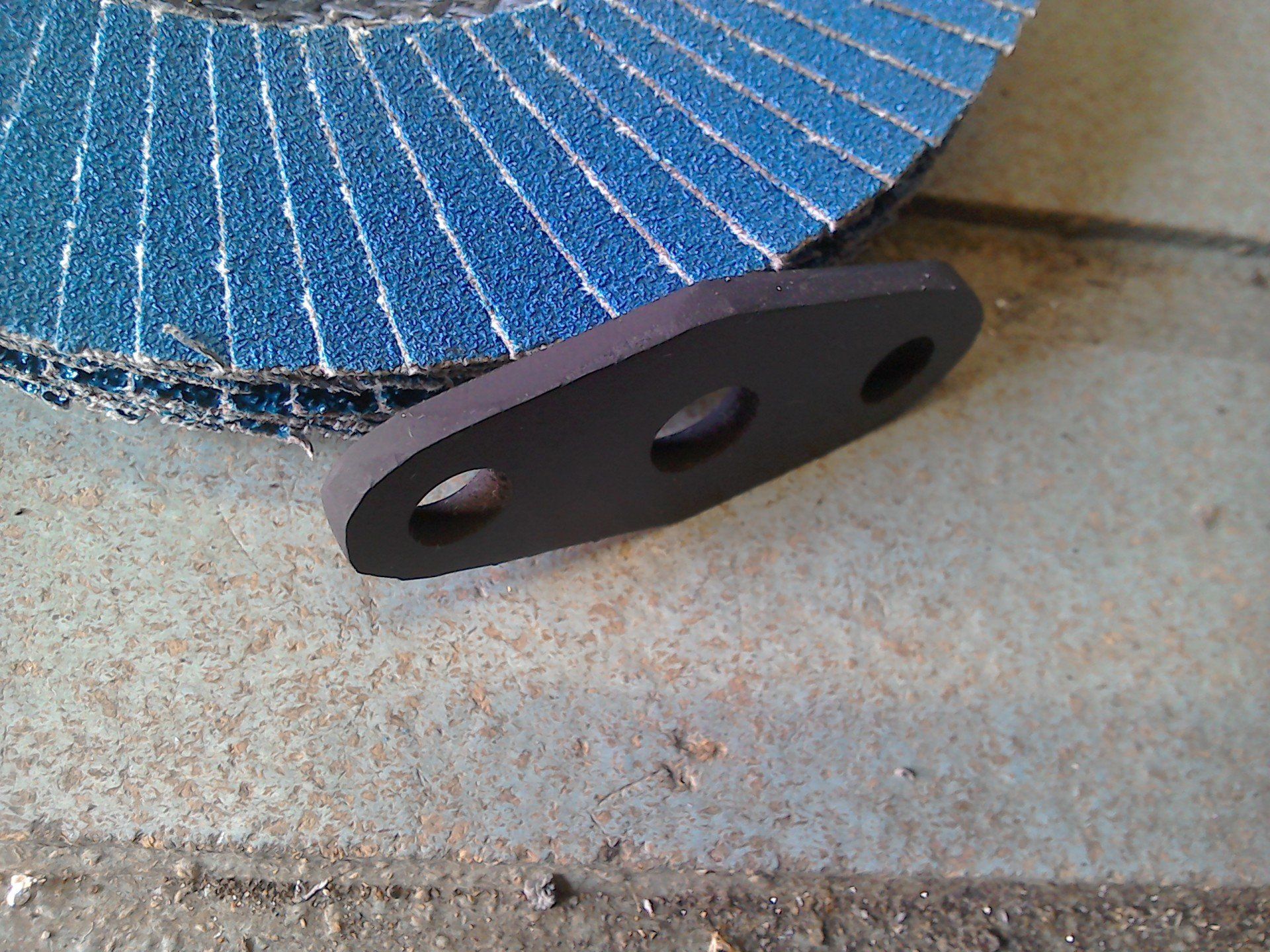

While they may be more at home on steel, they also work well on aluminium and wood (although these can clog the abrasive quite quickly and generate a lot of heat). Less obviously, they also make a good job of plastic, fibreglass (but again don’t let the work get too hot) seat foams, and stiffer rubber materials. The edges of the Viton gasket shown (below) were finished using a flap disc. The elasticity of this type of material makes it difficult to cut and finish neatly using a knife. A flap disc soon sorts this out.

An example of such a book is the ‘Nuts, Bolts, Fasteners and Plumbing Handbook’ by Carroll Smith, and this is a small extract from it: ‘Ok, so what actually keeps a properly designed and put-together bolted assembly tight? Let’s first discuss some of the things that do not keep it tight. Loctite does not keep it tight. Lock washers do not keep it tight. Safety wire does not keep it tight… In the final analysis, what keeps a bolted joint tight is the same force that clamps the part together - the residual tensile stress set up in the bolt during the tightening process.’

Basically when a bolted joint is tightened, the bolt is stretched (in tension) and the parts that are being clamped together are compressed. It’s these tensile / compressive forces that (hopefully) stop everything falling apart during use. To ensure that this all happens successfully, the bolt has to be stretched the required amount. There is no easy way of measuring how much we’re stretching a bolt, so we usually use the the next best thing and measure the force that is applied to the bolt during tightening.

So if we reach for our torque wrenches and toque to the manufacturer’s specifications everything will be Ok. Right?Well maybe. But we’ll talk more about that next week…